Tom Sciacca of Wayland: Sports versus the environment

Every organization has a culture and a set of values. Wayland’s values were embodied nearly 50 years ago, displayed proudly for all to see, on the wall of the then-new Middle School. Henry David Thoreau, Rachel Carson and Martin Luther King Jr. represent what we consider as a town to be really important.

Two of those three images focus our commitment to protect the environment. And for decades after they were painted Wayland was an environmental superstar.

We backed a strong Conservation Commission, nurtured the Sudbury Valley Trustees, and provided volunteers and financial support for regional environmental groups. We partnered with those groups and federal agencies to protect a large fraction of the town as conservation land, and by unanimous Town Meeting vote supported the national recognition of the Sudbury as a Wild and Scenic River.

Throughout that time one of our major goals was the protection of our drinking water, often regarded as some of the best in the state with absolutely no treatment. We always supported especially strong land and water protection because, as former DEP Commissioner and longtime resident, the late Russ Sylva, said at a Town Meeting, “Here in Wayland we sit right on top of our drinking water.”

But around the turn of this century things seemed to change. Development interests gained power. A new generation entered town with a focus only on the schools, not realizing that the beautiful green space they took for granted had taken great effort to preserve. That led to the creation of the failed Town Center shopping mall. And carpeting a large swath of land virtually on top of our best drinking water wells with plastic – the High School turf field.

Plastic is being increasingly recognized as a huge environmental problem. A New York Times report says “a 2016 World Economic Forum report projects that there will be more plastic than fish by weight in the oceans by 2050 if current trends continue.”

Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau is using Canada’s presidency of the G7 “to help stop the oceans from becoming massive rubbish heaps,” “particularly around plastics,” says a CTV report.

The Times report goes on, “Trillions of microplastics end up in the ocean, with seafood eaters ingesting an estimated 11,000 tiny pieces annually. Plastic fibers have also been found in tap water around the world; in one study, researchers found that 94 percent of water samples in the United States were affected. The impact on human health from direct exposure to microplastics is unknown.”

At the same time, Norway’s environment minister is proposing rules to address plastic pollution from artificial turf, recognizing it as an important source of microplastic emissions in Norway.

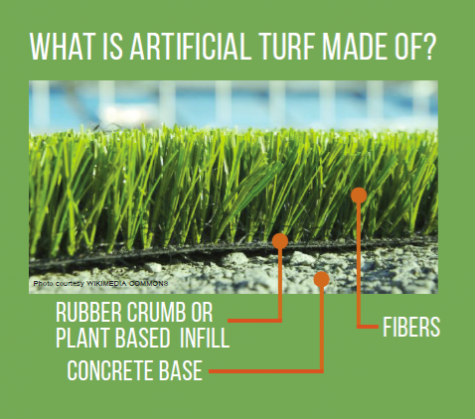

Wayland High School’s artificial turf field, installed in 2007, is wearing out. What does wearing out mean? It means the vinyl or polyethylene plastic strands simulating grass are being broken down by UV sunlight and abrasion from players’ shoes into small pieces and microparticles, and then being blown or washed away. Where does that plastic go? Into the marsh, and then the river. And ultimately, the ocean.

The same will happen to any replacement artificial field, no matter what is chosen as the infill propping those plastic strands up. There is a huge debate over whether the toxin-laden ground up tires commonly used as infill (including in Wayland’s field) actually release those toxins to poison players and the environment. And there are suggestions the problem can be solved with alternative infills, including pricey virgin rubber and coconut husks. But even if those alternatives are an improvement over old tires, they don’t solve the problem of the plastic that will eventually pollute the river behind the high school and the marshes around the Willowbrook neighborhood if the Recreation Commission has its way and a new artificial field is built at the Loker site on Rte. 30.

Ironically, taxpayers are being asked to spend millions of dollars more than otherwise necessary to renovate the high school facilities to protect the wells and the river.

“A significant driver in the design of the athletic improvement plan is rooted in the effort to enhance the protection of both the Happy Hollow Wells as well as the Sudbury River Watershed,” says the Annual Town Meeting Warrant.

In 2006 and 2007, the Boosters and the Board of Selectmen, the proponents of the then-proposed new artificial turf field, maintained adamantly that the field would be harmless to the wells. Concerns that town drinking water might filter through the huge bed of ground-up old tires on the way to our taps were dismissed as mere speculation. But in 2010, after the field was built, hydrogeological testing confirmed that under normal conditions about a third of the field drained to the wells. Under drought conditions that portion would increase. The testing to determine whether that drainage contained toxins, agreed to by the selectmen and Boosters as a condition of the final permit to build the field, was never done.

Several years ago, however, the Board of Public Works hired an environmental consulting engineer to check out the field. She found that the drainage system under the field designed by Gale Associates (the same firm that provided the study on which field usage claims are made to justify the need for artificial turf fields) didn’t work. And that there were masses of matted plastic strands in the swale to the north of the field. Again, that plastic pollution is independent of the tire shreds or groundwater drainage. In fact, much of the plastic is probably being blown off, rather than washed off, and is thus impossible to stop or contain.

There is a much cheaper and better way to protect the wells and the river. In 2011, DEP approved a Wellhead Protection Plan, the culmination of four years of effort by the Wayland Wellhead Protection Committee, which recommended that when the turf field wore out it be replaced by a grass field. Doing so would be far more effective in protecting the wells and river than all of the rebuilding and shifting being proposed. It would also save millions of dollars.

The soil under grass is what prevents contaminants, whether from humans or animals, from getting into the groundwater and to wells. The microbes in soil break down pathogens and chemicals, and trap other pollutants. And they work for cheap.

Ultimately voters at the ballot box and at Town Meeting will have to decide – what’s more important, pure drinking water and the environment, or more sports?

Tom Sciacca was a member of the Wellhead Protection Committee.Microplastic from a synthetic turf field:

http://wayland.wickedlocal.com/news/20180323/tom-sciacca-of-wayland-sports-versus-environment